Summer? What summer? The cold year of 2024.

The rest of the world records the hottest summer on record again, yet the UK, Norway and Iceland remain relatively cold with temperatures very rarely going above 20C.

‘What is nectar?’

One of the beginners says on lesson four of the course as we look at a frame taken from a beehive at the teaching apiary.

That stumps me momentarily. Why are they asking now? Haven’t they learnt what nectar is in the theory lessons?

We’re at the stage of the course where the beginners are now inspecting the hives with the tutors observing and guiding. One student has taken out a frame for the small group of 3-4 to look at in detail.

‘What do you see?’ I ask.

One or two reply with what I would expect; sealed and unsealed brood, pollen, bee bread, nectar, eggs and some sealed honey on the outer edges. Great!

Then one asks; ‘What is nectar?’

The others reply by telling them it’s the liquid that we see in the cells that the foraging worker bees have collected from flowers, brought into the hive and passed onto a younger bee for it to go and put it into a cell.

But, the question stays with me. What is nectar and where does it come from, and to compound this quandary that I found myself, which flowers are secreting nectar in a cold season like this one?

Beekeeping is all about problem solving…

Typically plants need temperatures between 25-35C for optimum nectar secretion, yet the bees were finding nectar as we saw in those frames. I also had a reasonable honey yield albeit about half of last years yield (2023 summer was also cold and wet, but May and early June was perfect for Hawthorn and many fruit blossoms). So where were my bees getting nectar from?

In 2016, I wrote quite extensively about nectar here:

At that time I had access to Pat Wilmer’s tome on Pollination and Floral Ecology. I bought my own copy and indeed the book that Pat says is the ‘bible’ of nectar; Nectaries and Nectar by Sue Nicolson et al 2010. I wanted to delve deeper.

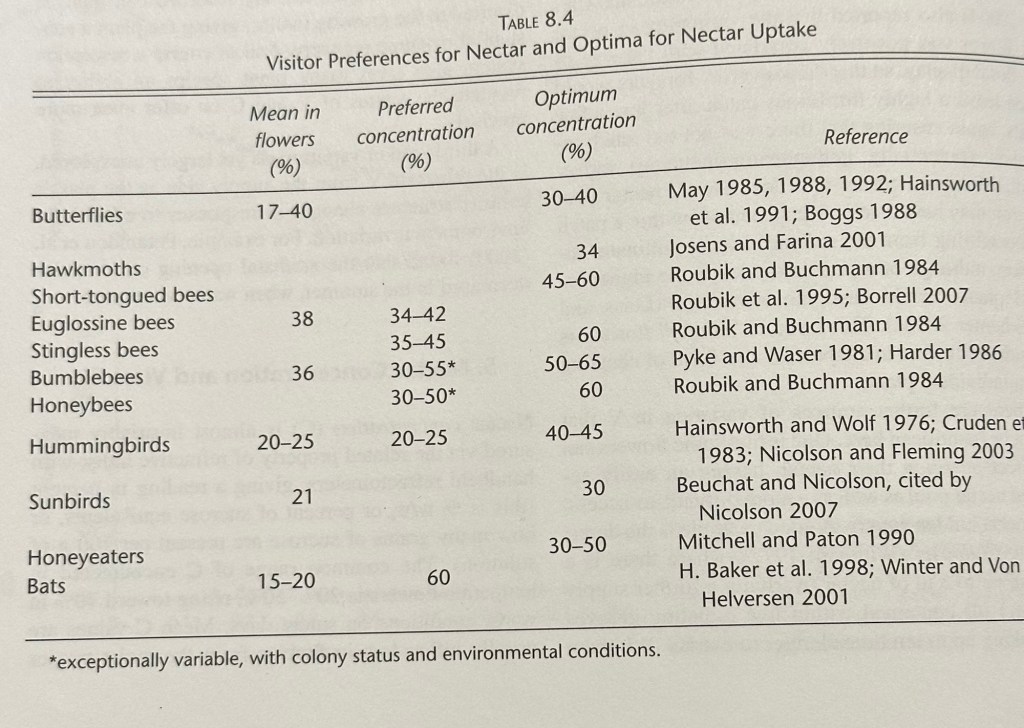

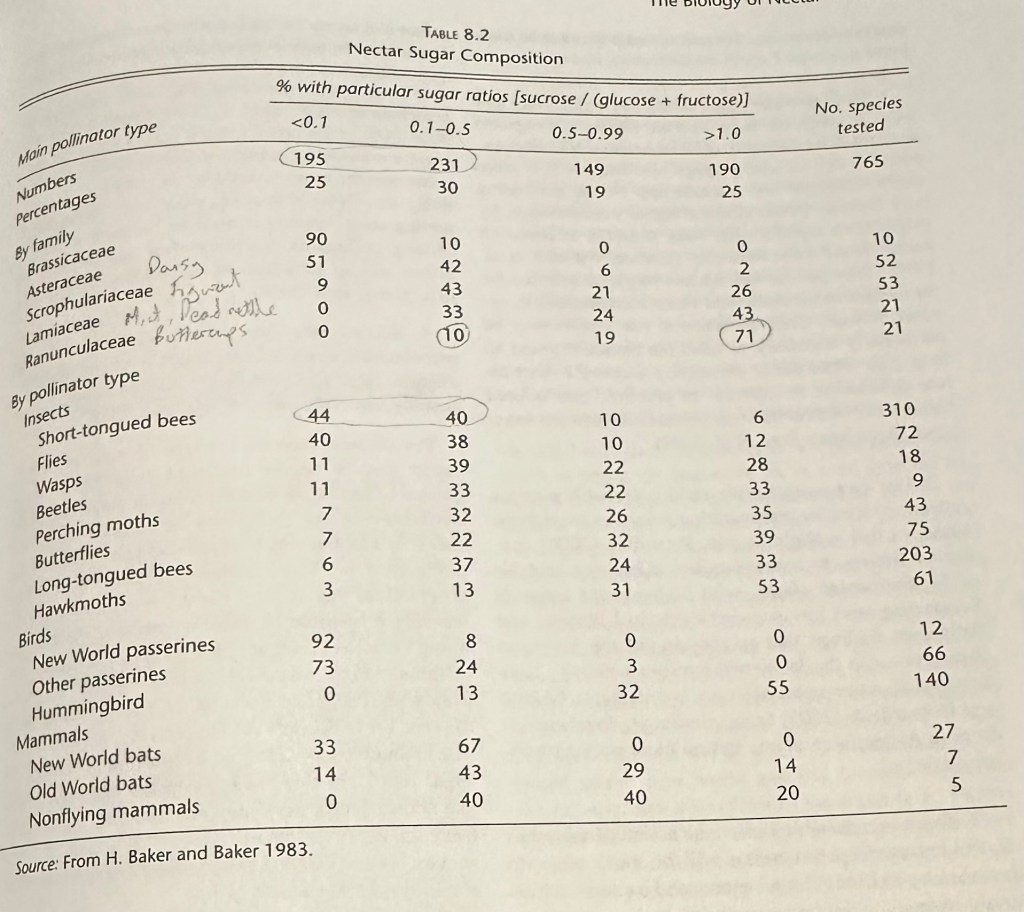

Of course, we are aware of the symbiosis that exists between angiosperms (flowering plants) and pollinators. As I work my way through Nectaries and Nectar this awareness becomes much more of an understanding of how nature is itself a superorganism. What we see is that plants fine tune themselves to the pollinators and vice versa. Plants can control the volume and sugar concentration of the nectar they produce to suit a particular range of pollinators. Honeybees have a relatively short tongue, and also a very sweet tooth; and as such prefer nectar concentrations of 50-60% sugar concentration. They also prefer hexoses (monosaccharides, Glucose and Fructose to Sucrose, although not exclusively). Indeed the plants that target honeybees as pollinators invert sucrose made from photosynthesis and either stored as starch or offered immediately. Inversion means using invertase to hydrolyse sucrose into its components glucose and fructose. The flowers that can typically provide this are ‘cup’ shaped and shallow.

Pollination and Floral Ecology, Willmer.P

Honeybees can manage to suck up nectar with a high concentration of sugars, but longer tongued pollinators can’t manage the viscosity, and so what we see is that the tubular shaped flowers typically offer lower sugar concentrations to allow those pollinators to pollinate them, e.g. buddleia.

A concentrated sugar solution becomes too sticky and viscous to rise up or be sucked up a long thin tube. The effect is not linear, since viscosity rises exponentially with concentration so that a 60% sugar solution is roughly 28 times as viscous as a 20% solution. There is therefore an optimum concentration for a given tongue length and type to achieve the best rate for acquiring calories.

The ability of plants to store nectar in starch is something that I feel is particularly relevant to those plants that are in symbiosis with honeybees. These plants can build up starch by photosynthesis until the time that they need to attract the bees for pollination. They can control the sugar content, the rate of refill and also invert the sucrose to the hexoses. For honeybees in the UK many of these plants fall under the Rosaceae family; blackthorn, hawthorn, pear, apple, crab apple, blackberry and many more. Other honeyplants include; rosebay willowherb, clover, ivy, himalayan balsam, heather among others.

My definition of a Honeyplant is a plant that can provide nectar at 50-60% sugar concentration over a period of time such that the bees collect an excess of nectar to be able to store it as honey. This means that there are vary large numbers of flowers and the nectar is probably comprised of the hexoses; glucose and fructose. Typically, honeyplants are weeds, trees (including fruit trees), OSR and some other such arable crops grown on a large scale e.g field beans, not flowering plants that we grow in our garden borders.

Pollination and Floral Ecology, Willmer.P

Some Rosaceae that flower before leaf emission certainly use vegetatively stored substances for nectar production. Radice and Galeti (2003) observed amyloplasts (organs that store and produce starch) in the nectary parenchyma (cellular tissue) of Prunus persica (Peach) before nectar production.

Another member of the Rosaceae family, Prunus spinosa (Blackthorn) flowers before it has leaves, yet beekeepers (in the UK) often observe honeybees foraging for both pollen and nectar. In this case the nectar has most likely come from stored starch.

The season of 2024 had little sunshine and so this build up of starch will have been slow. The apple trees in my orchard had very few apples this year, maybe the trees didn’t get enough sunshine to build up a decent offering of nectar to attract the honeybees and others.

By the end of the Spring and into the June gap, some colonies had to be fed syrup or fondant, they simply didn’t have enough stores. As we’d seen at the teaching apiary the bees had been bringing in nectar; enough to keep the colony ticking over in these Spring months. One telling sign was that we weren’t seeing swarm queen cells which we would expect in May. Colonies won’t swarm if the conditions aren’t right and that means they won’t swarm leaving a new queen with no honey stores.Now that the Spring flowers had gone, the colonies quickly consumed the stores that they had.

Bizarrely, the Spring of 2024 had apparently been the warmest on record…really…when I looked further into this I found that the nights had been warm and it was this that had elevated the average temperature. But, of course photosynthesis needs sunshine and although the nights might have been warm, there was very little sunshine during the day with temperatures usually below 20C.

There were fields of oil seed rape, OSR around my home apiary and the bees were clearly bringing in the pollen, but only small amounts of nectar. The OSR flower has two types of nectary. Nectar is derived partly from photosynthesis, producing dimorphic (male and female) nectar for 2-3 days. Both nectaries present nectar on the surface of the nectary and unconsumed nectar can be reabsorbed. (Davis et al 1986 writing about Brassicaceae).

The nectaries present themselves as inner and outer, with the inner nectaries producing more nectar than the outer ones which are ignored by the bees.(Calder Oilseed rape and bees 2015)

My guess with OSR is that the inner nectaries are the male ones and the bees will pick up the pollen and nectar before moving on to the next flower, brushing past the female outer nectaries and pollinating them as they do so. Or, possibly as the inner male nectaries are emptied of their nectar, then the bees move onto the outer female nectaries ensuring that cross pollination takes place.

Farmers often say that the OSR yield is greater if pollinated by bees; OSR is sold as being self fertilising.

In any case the bees didn’t gather an excess of OSR nectar this year, or indeed enough for me to take off, but what we see is that OSR derives its nectar from stored starch as well as directly from photosynthesis, very much a trait of the honeyplant, allowing it to provide nectar sweet enough to attract the honeybee and at a rate that makes it worth their while.

The story of the female nectary not being visited by the bees, also tells us that the bees can recognise the sweetest nectar, and not only the sweetest nectar, the sweetest hexose nectar (glucose and fructose as opposed to sucrose). It is why they will often ignore the nectar on offer by the hawthorn above the hives to go a mile away to get OSR nectar.

As the summer progressed, the blackberry seemed to be thriving. It can grow quickly in most years, but this year it seemed to be enjoying the cool climate. It flowered from May to August and I could see honeybees on the flowers often. The Rosebay Willowherb also flowered for around six weeks; I noticed bees flitting from flower to flower, mostly too quickly for me to take any decent photos. I could only assume that there was very little nectar. In the grass fields clover has been appearing more often in recent years and I feel that this may have contributed to providing nectar this year.

Honeybee foraging on Blackberry flower

Jakobsen and Kristjansson (1994) showed adaptive intraspecific effects for Trifolium (Clover), where clones from Iceland had optimum nectar secretion at 10C compared to Danish clones which peaked at 18C, the differences being heritable.

In recent years local farmers have moved from mineral fertilisers to green ones, mostly because of the enormous increased costs of the mineral fertiliser. As a result we are seeing clover in the fields again. I feel that it’s quite possible that the clover contributed to this year’s honey

Defoliation experiments conducted with Impatiens glandulifera (Himalayan Balsam) demonstrated that only a fraction of the day’s nectar secretion depends on the day’s photosynthesis, while another fraction must be mobilized from stored photosynthates in storage organs (Burquez and Corbet, 1998).

Late in the season of 2024, the honeybees were foraging on the Balsam along the waterways nearby for many days even though the temperature was below 20C most of the time, and yet they consistently brought in nectar (and pollen). An example of how a plant can build up reserves of starch to convert to nectar when the time is right for pollination. It also demonstrates again why beekeepers call such a plant a honeyplant.

There was no heather this year again, rumour had it that the heather on the Black Mountains had been devastated by Heather Beetle.

Many flowers manage secretion and reabsorption of nectar; to recover resources when nectar remains unconsumed and a means of management of nectar concentration. Reabsorbed nectar can be used again if necessary. Some plants reabsorb remaining nectar once pollination is complete. Some plants don’t reabsorb nectar at all as in Hedera helix (Ivy) where nectar can granulate on the flower. Ivy is a plant that lives very much in the shade of other plants and so it is probable in my opinion that there is a build up of starch throughout the season until it needs foragers late in the season to pollinate.

Honeybee foraging on Ivy

Later on into September 2024, the Hedera helix (Ivy) offered pollinators pollen and nectar, producing nectar for 5-6 days. The bees took this opportunity to bolster their stores.

In general we see that short tongued bees much prefer hexose dominant nectar as offered by Brassicaceae and Asteraceae (Daisy) among others, tending to avoid those flowers that offer sucrose dominant nectar for example from Ranunculaceae (Buttercups) (P.Willmer 2004).

Pollination and Floral Ecology, Willmer.P

This might explain why we rarely see bees foraging on buttercups in the fields in this area.

Temperature can affect overall production in different fashions that are generally assumed to be adaptive. For example in Thymus, nectar, volume, concentration and sugar content all increased with temperatures up to 38C (as long as there was no water stress). Water availability is critical, plants tending to produce their highest crop after a good rainfall.

I have learnt so much more about how nectar is produced and how in ‘Honeyplants‘ in particular nectar can be stored in starch for later usage. Plants can manage the nectar volume and concentration that they produce to match their preferred pollinator. On top of that you’ll see below that plants ‘listen’ to the buzz of pollinators and can recognise their preferred pollinator and adjust the nectar offering accordingly. I have added my own observations as a beekeeper to help interpret the research results. As a result it is clearly possible for the honeybees to get an excess of honey in a cold year like 2024 albeit a small excess.

I took off a small excess of honey this year, not really expecting any excess most of the season. In my opinion the excess honey came mostly from Blackberry/bramble, with some coming from clover and Himalayan Balsam. I’m also lucky to have ‘drawn’ combs in the frames in the supers, so the bees didn’t have to draw any comb this year which meant that they could simply fill the comb that was given to them.

Over 30 hives, I have had an average of one super per hive excess honey.

Other compounds in nectar include; inorganic ions, amino acids, proteins, lipids, organic acids, phenolics, alkaloids, terpenoids, the latter probably with antimicrobial benefits (Raguso, 2004). A reminder that honey is not just carbohydrate!

The holistic beekeeper must value all aspects of the honeybee in order to gain a more full understanding of how nature has evolved to work in such close symbiosis.

———————————————————————————————————–

Flowers hear the pollinator. BBC the genius of plants, National Geographic https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/flowers-can-hear-bees-and-make-their-nectar-sweeter

I stumbled across a documentary on the BBC, the Genius of plants, in which Lilach Hadany explains how the Evening Primrose can ‘hear’ sounds and is actually in tune with the buzzing of bees. When it detects the bees buzzing the petals also vibrate and within three minutes, the sugar concentration of its nectar is increased from between 12 and 17 percent to 20 percent.Honey bees in particular have a sweet tooth and it’s as if the plant knows this. The scout bees will have informed the colony of this nectar source and within minutes many more foragers will be taking the nectar and pollen, pollinating as they go. As the numbers increase then many foragers will be getting nectar at this higher sugar concentration.

The shape of the flower lends itself to being a receptor of ‘waves’, in this case sound waves from bees at 200-500Hz. It follows that other flowers should behave in a similar way. Of course flower ‘bowls’ or receivers come in various sizes, but the sound frequency from the bee is also over a quite a wide range.

Why would it not be the case that ‘honey plants’ those plants that provide such a lot of nectar because of their abundance are not also behaving like this to ensure that they are being pollinated.

It makes a lot of sense for the flowers to only increase their nectar offering when they hear the bee, otherwise they may be giving their sweeter nectar away to other insects that don’t necessarily pollinate very well. Bumblebees are known to fly between different types of flower on a foraging flight. Whereas the honeybee will remain at a source of nectar for as long as it remains. Not only that, they will return at the same time the next day and so on.This symbiosis makes for the most efficient pollination.

Sound is so elemental to life and survival that it prompted Tel Aviv University researcher Lilach Hadany to ask: What if it wasn’t just animals that could sense sound—what if plants could, too? The first experiments to test this hypothesis, suggest that in at least one case, plants can hear, and it confers a real evolutionary advantage.

Hadany’s team looked at evening primroses (Oenothera drummondii) and found that within minutes of sensing vibrations from pollinators’ wings, the plants temporarily increased the concentration of sugar in their flowers’ nectar. In effect, the flowers themselves served as ears, picking up the specific frequencies of bees’ wings while tuning out irrelevant sounds like wind.

For plants exposed to playbacks of bee sounds (0.2 to 0.5 kilohertz) and similarly low-frequency sounds (0.05 to 1 kilohertz), the final analysis revealed an unmistakable response. Within three minutes of exposure to these recordings, sugar concentration in the plants increased from between 12 and 17 percent to 20 percent.

A sweeter treat for pollinators, their theory goes, may draw in more insects, potentially increasing the chances of successful cross-pollination. Indeed, in field observations, researchers found that pollinators were more than nine times more common around plants another pollinator had visited within the previous six minutes.

Though blossoms vary widely in shape and size, a good many are concave or bowl-shaped. This makes them perfect for receiving and amplifying sound waves, much like a satellite dish

To test the vibrational effects of each sound frequency test group, Hadany and her co-author Marine Veits, then a graduate student in Hadany’s lab, put the evening primrose flowers under a machine called a laser vibrometer, which measures minute movements. The team then compared the flowers’ vibrations with those from each of the sound treatments.

“This specific flower is bowl- shaped, so acoustically speaking, it makes sense that this kind of structure would vibrate and increase the vibration within itself,” Veits says.

And indeed it did, at least for the pollinators’ frequencies. Hadany says it was exciting to see the vibrations of the flower match up with the wavelengths of the bee recording.