For the love of honey

One of the attractions and wonders of beekeeping is that it is work against the odds.

Working with three most unpredictable resources; the climate, the plant environment and an insect that can become angry and sting you, the beekeeper does his best to manage these resources as best he can. No season is the same as past seasons, no colony of bees the same as another. This is also the ‘magic’ of beekeeping. All plans are severely tested and changed many times; you hear ‘experienced’ beekeepers boasting that they didn’t lose a swarm this year….but are their bees happy bees as a result….did the bees swarm, but they didn’t notice? The reality being that none of these natural resources, the bees, the climate and the plant population are fully understood, and so the beekeeper develops his own solutions to his local problems. As a result, beekeepers, when asked a question, will invariably give variations on an answer to each other. Who is right and who is wrong is something the new beekeeper must take away and test for themselves, given the basic tools to work with.

The year 2022 or indeed the 12 months from October 2021 to October 2022 was once again different and a wonder to behold. The ivy was so generous towards the end of 2021 that several bee colonies gathered a surplus to be harvested, Ivy granulates quickly to become almost rock hard. Some experienced beekeepers aim to feed syrup before the ivy flowers to fill the brood chamber before it can be filled with the ivy; bees can struggle to liquidise the solid honey in winter and end up perishing by starvation. My experience is that the bees mix it with the honey I have left for them, often storing it on the outer edges of the box(es). In contrast to late 2021, the ivy hardly flowered in late 2022.

The summer of 2022 was a very hot one; maybe this affected the ivy. Not so the heather! My bees will get heather honey 1 year in 4 or 5; the July of 2022 was so hot and dry, experienced beekeepers were saying that there would be no heather honey this year…too hot and dry. What happened was the exact opposite; the bees traveled far and wide to gather record levels of ling heather honey. In my case, I had already taken off the summer honey in late July, extracted the honey and put the ‘wet’ supers back onto the hives for the bees to clean out. I then took a holiday in early August, only for a fellow beekeeper to message me saying, ‘I hope you put supers on the hives Chris!’ I hadn’t gone far, only north Devon to fish the big Spring tide, but remained there as it was such fantastic weather; the sea was a delight to swim in.

On my return, the bees were still bringing in heather; you learn to recognise when there is a ‘flow’ of honey taking place, the bees leave the hive as if on a mission, like little charged bullets, and return in a similar way, woe betides anyone who gets in the way, and of course, you can smell the scent of the flower which fils the apiary!

Earlier in the Spring, the tree blossoms arrived in their natural order as time progressed, but this year there were some fields of oilseed rape near my colonies, and the OSR takes precedent over anything else; the bees go wild for it! (see later notes). So for several weeks, the bees were collecting the OSR at the expense of some of the more aromatic tree blossoms, e.g. Hawthorn. As soon as the fields started turning from yellow to green and I could see that the striking yellow pollen on the hindlegs of the worker bees was diminishing in number, I took the supers off and extracted the OSR honey. Like ivy, OSR will granulate quickly to a very hard white honey. Now, what to do with this OSR honey? At the RWAS show this year, the best on show was given to a pair of very light coloured, almost white, granulated honey jars. Quite an interesting decision….surely the judges hadn’t given this to rock hard honey. Indeed not, the winning beekeeper let on to me that this was OSR, but had been creamed straight after extraction…and so a whole new line in honey was added to my repertoire that of ‘soft set’. All honey will granulate at some time or other and it is often said to be a sign of good quality honey and when honey granulates it can be quite ‘grainy’. However, OSR honey has a very small grain, making it very smooth, that is when it’s not rock hard. With good timing, OSR honey can be extracted and then creamed to make soft set or used to ‘seed’ other clear runny honey to make more soft set honey. By using OSR as a seed with other honey a very palatable soft set honey can be produced.

In the calendar year from Oct 2021 to Oct 2022, I had extracted honey four times; Ivy, OSR, summer honey of blackberry and rosebay willowherb, and finally, ling heather. In contrast to the year before when I extracted only the summer honey. Two of these honeys granulating almost immediately.

I reread my books relating to honey and found that I learned some new things from this year’s experience, as follows:

Collecting the nectar. A foraging bee flies at about 13-15mph, at a height of between one and eight metres above ground. If the wind is much above 15mph she won’t go out. The forager takes with her enough nectar from the hive to enable her to reach the crop she is working. She flies direct to the crop and visits one flower after another until her honey sac is full. The flower of the tulip poplar holds so much nectar that the bee can fill her honey sac in a single visit, but this is unusual. Usually, a bee visits between fifty and a thousand flowers on a trip, but it can be several thousand. During a good flow from sweet clover when the hive was gaining 5lb a day, an average foraging trip was found to be 34 minutes, and the next year when the flow was less good, the average was 49 minutes. The average number of trips was 13.5 during the good flow and 7 during the poor one. When there is no rich flow, each forager probably makes less than 10 trips a day, and may make only (1. Crane, E. 1980 A book of honey, Oxford University Press)

Converting the nectar into Honey. Honey is made in the hive, above and around the brood nest, where the temperature must be regulated quite closely at 34-35 degrees C; the temperature of the honey is usually within a few degrees below 35C. When a foraging bee arrives at the hive carrying the nectar, it will have already been diluted with saliva containing secretions from several glands, especially the hypopharyngeal glands, which contribute the enzymes used in elaborating honey: invertase, diastase and glucose oxidase. The sugar concentration of nectar varies widely between plants. Acacia having over 60%, relatively little water needs to be evaporated, but to produce a kg of clover honey, more that 2kg of clover nectar containing 40% sugar must be collected. Nectar containing as little as 13% sugar is hardly worth collecting, and indeed bees do not normally collect it except in early spring when they need the water in it t dilute stored honey for brood rearing.

When the honey has been evaporated to the lowest possible water content, 17-20% according to atmospheric humidity and temperature, the bees fill each cell completely and cap it with beeswax, which prevents absorption of water by the hygroscopic honey, and the potential risk of fermentation.

Between the stages that the nectar becomes honey, the enzyme invertase bringing about chemical changes leading to a higher sugar content than could be achieved without the enzyme reaction action. This is the ‘secret’ of honey. Invertase ‘inverts’ the sucrose into glucose and fructose. At the temperature of the honey combs in the hive, around 30C, the solubility of glucose in a solution of fructose increases abruptly if the fructose concentration is raised above 1.5 grams per gram of water. The gram of water can then hold in solution, as well as the fructose, 1.25g of glucose, which is 50% more than a dilute fructose solution can carry. (1.5g + 1g =2.5g, 1.25g is thus 50%) This high glucose solubility does not operate at higher temperatures nor at lower ones. The bees are able to produce a more concentrated solution of sugars than could otherwise be obtained, a super saturated solution containing only around 18% water. As a result, the stored honey is resistant to spoilage by fermentation and is a high energy pack occupying minimal space. This is the magic of honey

Of the other two enzymes produced, glucose oxidase reacts with glucose in the dilute stages of honey production, forming gluconic acid, the major acid in honey and hydrogen peroxide. The hydrogen peroxide protects the partly formed honey against bacterial decomposition until its sugar content is high enough to do this.

Pollination. Commercial honey producing colonies are managed so that they have a large nectar foraging force when the flow is on. Colonies for pollination should have a large amount of brood, and thus a need for much pollen, and insufficient pollen stores in the hive. This will produce a large number of pollen foragers, which are usually more effective pollinators of most plants than nectar foragers. The tendency of most foraging bees to continue working on the same crop instead of changing to another one, imposes an important rule on beekeepers moving bees to a crop to pollinate it: wait until the crop is in flower before moving the bees, and release them from their hives as at a time of day when pollen is available from the crop. Otherwise, the bees are likely to find other sources of nectar and pollen in the locality, and become fixed on them, ignoring the crop to be pollinated even when it is in full flower. (1)

It’s an important thing to note when taking bees to apple orchards where there is dandelion growing amongst the trees…in the past, the orchard owner would mow the grass to remove the dandelion as the bees much prefer it to the apple…as I don’t move bees myself, I don’t know if the modern orchard owner is aware of this….somehow I doubt it. I doubt many beekeepers are really aware 😉

The tendency for bees to continue to forage on the same crop is the reason that we sometimes get a different honey from one season to the next. This year, it is the reason that I didn’t get any hawthorn honey as the bees preferred the OSR, and as it started to flower before the hawthorn, then the bees wouldn’t switch to it as long as the OSR was flowering, even if the hawthorn was directly above the hive!

Nectar. The attractiveness of different nectars to bees depends on the total sugar concentration and to a certain extent on the proportions of different sugars. Botanists measure the nectar productivity of a plant by its sugar value, the weight of sugar (in mg) secreted by one flower in 24 hours, the sugar value is fairly constant for any one plant species. Of the species that have been assessed (Europe), the following have very high values (all 3mg per flower in 24 hours): two limes, Tilia platyphylos and Tilia cordata; a sage, Salvia leucantha, rosebay willowherb, Chamaenerion angustifolium, gooseberry, Ribes uva-crispa and borage, Borago officinalis. (1) I would add OSR and blackberry/bramble to this list in my locality.

The total amount of honey obtainable from a plant depends on three factors: the sugar value as above, the number of flowers in a given area, and the number of days the flowers are secreting nectar. The following are a few of the plants for which a honey potential of more than 100kg/ha has been calculated, although in practice, not all of them would cover an area as large as an acre or a hectare; borage, dandelion, acacia, rosebay willowherb and small leaved lime. (1) Again I would add OSR, blackberry and Himalayan balsam based on Eva Crane’s criteria.

Sweetness of Honey All honey is sweet, since around 80% of it consists of sugars, but some honeys taste sweeter than others because sugars differ in their sweetness. Some of the extra sweet honeys include Himalayan Balsam, Impatiens glandulifera which easily becomes naturalised in suitable damp places; it spread rapidly in the 1960s in Europe, and has reported to yield up to 20kg of honey per colony in England, Germany and Switzerland. I include this as my bees collect nectar from it late on in the season, but of course, being a foreign plant, there are teams of folks locally who dedicate their time to destroying it as it supposedely stops natural plants from growing…only they know what those plants are or might be. As a result I don’t get any honey from it.

Ling heather. A few honeys have abnormal flow properties. Ling heather is well known for its gel like consistency: it will not flow sufficiently for a centrifugal extractor to remove the honey from the cells. If the honey is agitated, it becomes more liquid and will flow. This property, known as thixotropy, is due to the relatively high content of certain proteins in the honey; chemical analysis shows a protein content of up to 1.86% (2); if the proteins are removed and added to another honey, the thixotropic character is transferred with them. Other honeys that are thixotropic, by reason of their protein content are manuka from NZ and karvi from India. Of the many minerals in honey, there is a larger quantity of potassium than any other and this increases almost ten fold in darker honeys. (1)

Lime trees. Observation shows that bees often work trees early in the morning for honeydew but later in the day, when the honeydew dries, the trees are often neglected in favour of clover or blackberry. (2. Sawyer. R. Honey Identification 1988. Cardiff Academic Press)

Granulation of honey Honey appears lighter in colour after it has granulated; this is due partly to the transparency of liquid honey and the opacity of granulated honey. Only a very thin layer of granulated honey can be seen at once, and a layer of liquid honey of this thickness would also look much lighter than a jarful. The colour of any one sample of honey when it granulates depends on the crystal size; the finest crystals give the lightest appearance.

All honeys are liquid when produced by bees, at room temperatures, which are 20C below hive temperatures, crystallisation (granulation) is quite likely to start within some weeks or months (more rarely within days or years). The first sugar to crystalise out of solution is glucose, the most useful ratio in determining this is the glucose to water ratio. An index used earlier is the fructose to glucose ratio; if this was above 2 the honey wouldn’t granulate. But this takes no account of the amount of water in the honey, in which both the sugars are dissolved. Honeys with less than 17% water are more likely to granulate than those with 18%; those with more than 19% may well be in danger of fermentation. Honeys containing less than 30% glucose rarely, if ever, granulate.

Honeys with high glucose/water ratio fairly quickly become completely granulated; examples are; OSR, dandelion and ivy. Rapid crystallisation normally produces a fine granulation producing a smooth, light coloured honey

OSR. Bees will work OSR from early in the morning to late in the evening. Nectaries can take up to 30 minutes to refill and contains 30-40% The OSR flower has two inner and two outer nectaries, the inner nectaries producing much more nectar than the outer ones; the bees preferring to take nectar from the inner ones ignoring the outer.

Usually, within the hive, crystalisation does not occur because the temperature is either too high or, perhaps surprisingly, too low, or because stores are used up before their condition can change. With OSR, however, crystalisation is almost certain to occur around ten days after capping.

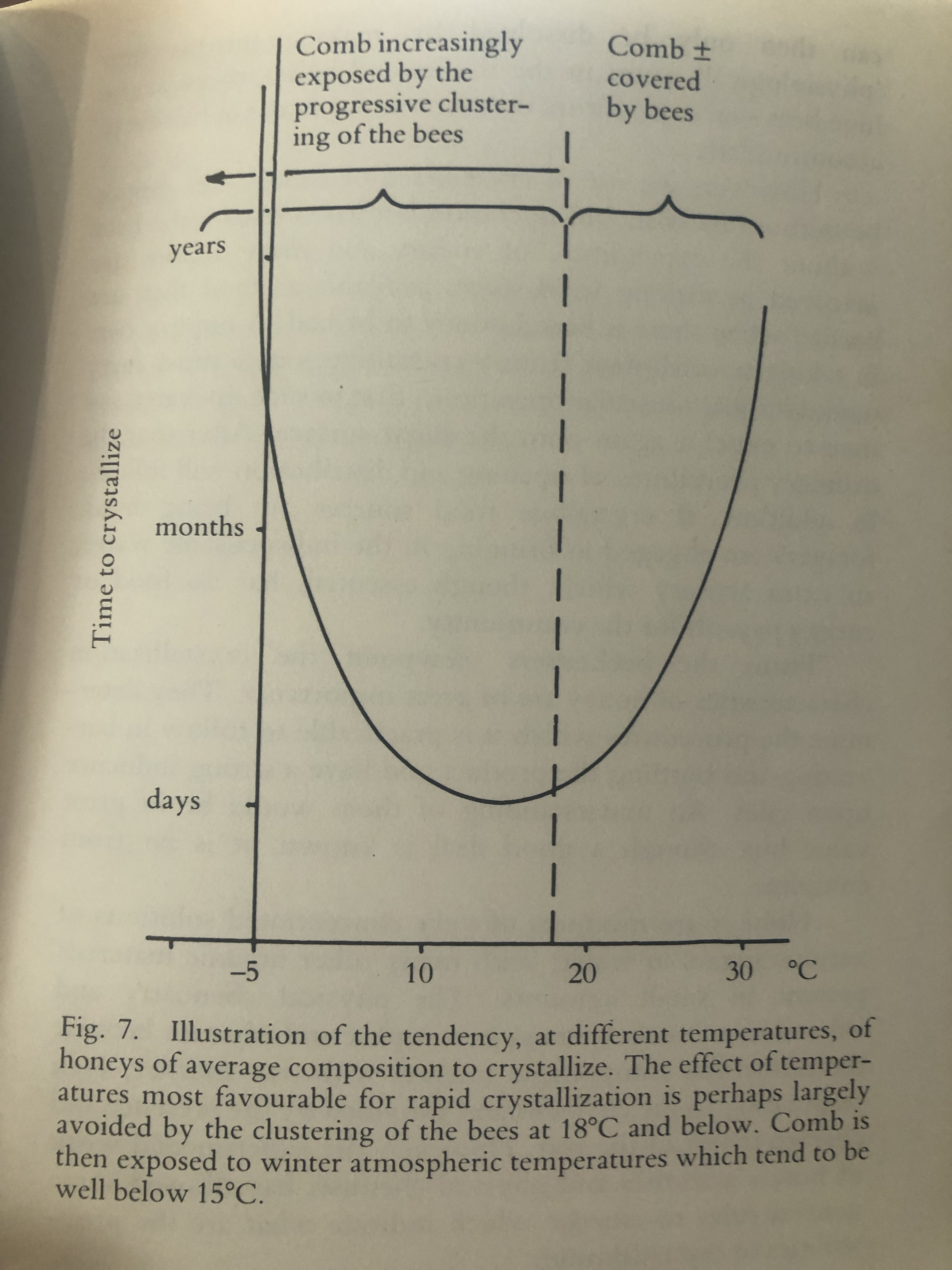

Observations made upon honeys of average composition show that crystalisation occurs in them most rapidly at 14C or 15C. Either side of that temperature, the tendency to granulate declines. At 10C, it is retarded, at 4.5C almost stopped and at -1C, no sign of crystallisation is seen even afer 2 years. But if honey is already granulated at 14C, no amount of cooling thereafter will reduce the granulation but, on the contrary, will consolidate it.

It is very striking to notice that the bees themselves also react strongly at 14 or 15C. At about that temperature their behaviour undergoes the marked changes leading to the starting of the formation of compact winter clusters. (3. Calder A. Oilseed Rape and Bees, 1986 Northern Bee Books)

This is fascinating, it’s as if nature had intended this to happen, as temperatures dropped with the onset of winter then much of the honey in store would remain liquid. What we are seeing though is that winters are getting warmer and we see mid winter temperatures of 10C or more most winters, either as a natural cycle of climate or because of climate change. The main honeys that the bees produce in my locality are the ones that granulate very quickly anyway. Of course the bees can manage this, but it takes extra effort on their behalf.

In summary, 2022 was an exceptional year; on top of the summer honey of mainly blackberry and willowherb, the bees also had good strong flows on ivy, OSR and Ling heather….I must have been extracting honey for over two months this year…on and off.

Also what is very apparent is the small number of plants and flowers that bees can produce enough excess honey for man to remove some for his own use. Of course, I plant many flowers both for my pleasure and also for the pollinators and there are many wildflowers that still manage to thrive in the hedgerows, but the reality is that for reasons explained above the bees can never collect enough nectar to make more than a few grams of honey from them. (Plants in my locality by nectar and pollen)

I note that a local university has devoloped a clover that adds more nitrogen into the soil, but doesn’t secrete nectar…what is man up to. These lovely green fields are even more of a desert to nature than they ever were. That’s progress for you.

Nature, the climate and that lovable little insect.

In memory of my dad Richard Cardew 21/2/39-5/12/22 – Telling the bees

The Lake Isle of Innisfree – William Butler Yeats

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

Well done, Chris. You have brought together your own experience and excellent and varied research. I hope that all the membership will read and absorb this fascinating information.

Best, David

Sent from my iPad

>

Thank you David.